Fort Meade Maryland Internment Camp

Today, Fort Meade is the headquarters for the NSA and other intelligence and cybersecurity agencies. The 8-square-mile campus is also home to 10,000 military personnel, some of their family members and 'civilians'. The more than 8,000 contractors who work on the post must go through checkpoints, including dogs sniffing.

"Fort Meade is home to more than 90 support organizations from all four

armed services, ranging from the National Security Agency to the

renowned U.S. Army Field Band. Centrally located between the major

metropolitan areas of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., Fort Meade, MD has

grown over the years into a military and social destination, serving

every possible need of modern military personnel." [http://meade.corviasmilitaryliving.com/]

Images Courtesy of Randy Houser

- A timeline of Fort Meade in the war:

-

- Dec. 7, 1941: Pearl Harbor attacked

Feb. 19, 1942:

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, designating

“exclusions zones” for noncitizens living in military areas on the

coasts.

March 18, 1942: War relocation camps created

Sept. 15, 1942: Fort Meade receives its first Japanese, Italian and German internees.

Sept. 7, 1943: Fort Meade accepts its first prisoners of war: 1,632 Italians and 58 Germans.

Sept. 2, 1945: Japan formally surrenders; the war ends

December 1945: The first German POWS are released.

July 1946: The Fort Meade POW camp closes

1947: The last POW is released from Ellis Island

August 20, 2013

Capital Gazette - The stone ashtray marked “Seagoville” was a place to throw paper

clips in the family home — and John Heitmann’s first clue his father had

a secret he took to the grave.

Heitmann’s quest for the truth led him to the National Archives,

where he discovered Alfred Heitmann’s secret: He spent World War II in

internment camps, including one at Fort George G. Meade, and also a

family camp in Seagoville, Texas, a suburb of Dallas.

“When I was at Johns

Hopkins University, we even drove past Fort Meade. He never said a

thing,” says Heitmann, now a university professor in Dayton, Ohio.

Neither did his mother.

Heitmann’s story is a

common one among the descendants of European immigrants labeled threats

to national security after the United States entered World War II.

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Fort Meade Prisoners of War

Prisoners of war sewing clothing in an internment building on the grounds of Fort George G. Meade.

Many are stories of shame and fear.

For seven decades Fort

Meade’s internment camp has been kept a secret, both to many of the

families of those imprisoned there and to the public.

The Army post’s website

doesn’t mention the 30-acre facility that housed hundreds of Japanese,

Germans and Italians, most of whom had built successful lives in this

country but had not yet become citizens.

The National Archives,

however, records the stories of men pulled from their families at

gunpoint and denied due process by local Alien Hearing Boards that

sentenced them to prison camps.

They were not given a

trial, informed about their accusers, presented with the evidence

against them or afforded legal representation. When the hearing boards

met, the FBI unveiled often-preposterous claims originating from

disgruntled business partners, angry neighbors and jilted lovers.

It didn’t take much to

convince these local boards that 120,000 Japanese, 11,000 Germans and

3,000 Italians were a threat to the country they called home. Some —

more than 2,700 Germans alone — were returned to their native countries

against their will in exchange for Americans imprisoned abroad.

Others were sent to camps like the one at Fort Meade.

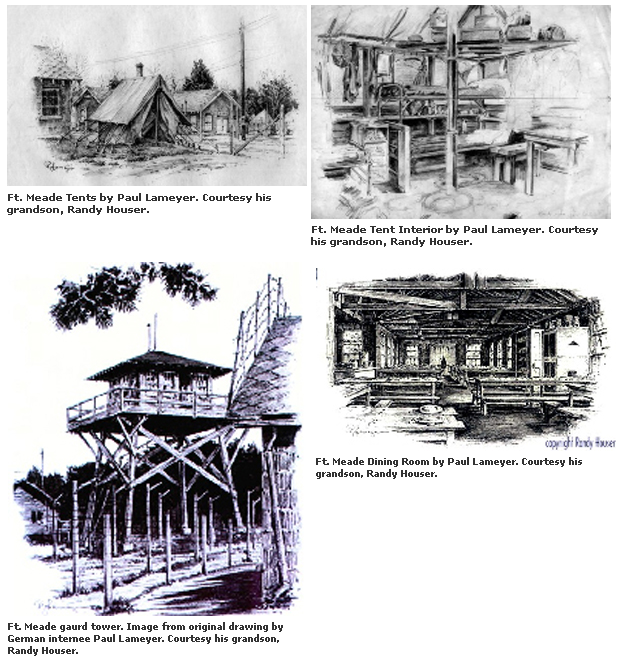

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Fort Meade Prisoners of War

A sketch of the grounds drawn by German internee Paul Lameyer during his confinement at Fort George G. Meade. The water tower is still standing.

Allowed only what they

could carry, they ended up inside confined quarters, still professing

their loyalty to the United States. File after file at the National

Archives reveals their attempts to be reunited with families and their

frustration at being branded traitors.

One such story is told in

memos by Iwajiro Noda, who immigrated from Japan to New York City in

1917 and married an American woman. He owned a profitable business,

Japan Cotton and Silk Trading Co., and had fathered a daughter who was

attending Goucher College in Baltimore when the United States joined the

war.

He was handcuffed and

taken to Ellis Island — the East Coast processing center for internees,

and, ironically, the place where many of the same immigrants had gotten

their first taste of democracy.

Noda ended up at Fort

Meade, where he wrote of his “loyalty to the United States of America, I

being a firm believer in American way of life, and also because I owe a

great deal to this country ...

“I have been a strictly

law-abiding resident of this country, always having never engaged in any

activity whatsoever inimical to the interest of USA, and further it is

my earnest desire to remain so all through the future.”

He begged to be released

because “the present state is undermining the health of my wife, who has

been forced to receive constant medical care.”

His plea fell on deaf ears. In April 1942, Noda was forced to liquidate his trading company after his bank account was frozen.

Nonetheless, he initially

declined repatriation to Japan. But one year later he gave up his dream

of living in America and sought to return to his native Japan without

his family.

The attention given to

the plight of Japanese-Americans during the war has overshadowed the

similar plight of German and Italian immigrants, something Randy Houser

and Cornelia Mueller are beginning to understand.

Their families kept

secret the story of relatives who were in the internment camps — a story

they are uncovering only now, through extensive research. They and

others are pooling their resources to finally share the story with the

public.

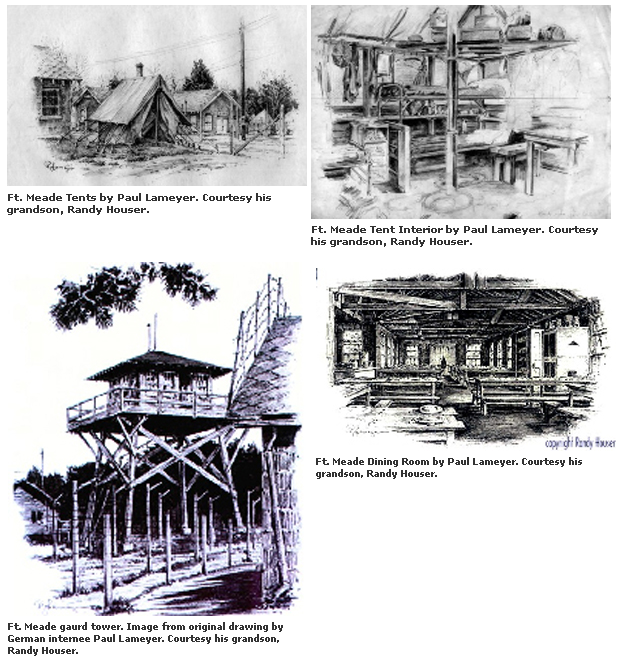

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Fort Meade Prisoners of War

A line of tents that housed internees or prisoners of war at Fort George G. Meade during World War II.

Mueller, who lives in Catonsville, says her father’s last words to her on his deathbed started her search for the truth.

At the National Archives,

she discovered that he was drafted into the U.S. Army at the start of

the war, but declared an enemy alien when he said he couldn’t fight the

Germans.

“He had family there,” Mueller says. “But it was the wrong answer.”

The files, she says, show

he was threatened by government authorities who told him to never speak

of his experience in the internment camps — a promise he and others

kept to their deaths, out of fear of being re-imprisoned.

Mueller thinks the

threats were intended to keep the information from reaching the enemy,

who held American prisoners. But former internees refused to talk about

their experience even long after the war ended.

Houser’s grandfather, Paul Lameyer, who immigrated to the United States in 1925, had been disowned by his family.

A successful architect,

he had lost his job during the Great Depression and split up from his

wife. When the FBI began to round up immigrants, his family, according

to what Houser dug up at the National Archives, eagerly provided false

information.

Houser, a former

Annapolis businessman who now lives in Charleston, S.C., says his mother

remembers that when she was 13, her father returned to their house

after the war ended. “He had a suitcase full of drawings, but she (her

mother) wouldn’t take him in,” Houser says.

Lameyer returned alone to Germany, where he died at age 61.

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Courtesy of Randy Houser

Fort Meade Prisoners of War

A sketch of the internee dining hall drawn by internee Paul Lameyer during his confinement at Fort George G. Meade during World War II.

Many of the drawings in his suitcase were of internment camps, such as the one at Fort Meade, Houser says.

Bob Johnson, Fort Meade’s

historian, thinks the internees were treated worse than prisoners of

war because they knew the language and were more of a threat if they

escaped. Most of the POWs couldn’t speak English and couldn’t easily

blend in with the civilian population.

The Japanese internees

were allowed to wear civilian clothes, but the Germans and Italians were

issued tea-green khakis with “P.W.” on the back.

Many of these internees

had been affluent. Now they had to make do with one winter coat and two

pairs of military boots. They were assigned to five-men tents — or

“hutments” — reinforced with wooden walls. A Sibley stove in the center

was the only source of heat; a 40-watt bulb the only source of light.

The camp was guarded by

soldiers on 30-foot towers who were armed with shotguns and Thompson

submachine guns. An internal memo raised concerns that any gunfire could

easily hit the well-traveled road on the west side of the fort, but the

soldiers won the argument and got even more firepower.

One document in the

archives reveals that an internee was wounded by a stray bullet fired by

an American soldier on a nearby firing range.

Internees were allowed to

send two letters a week to five people they designated. All letters

were censored and had to be “clear in meaning” and not of “inordinate

length.” Censors arbitrarily edited “ambiguous” language and delayed

delivery for weeks.

If visitors could afford

the long train ride to Fort Meade, they were allowed 25-minute meetings

twice a week. They had to speak in English. Few came.

Doctors found that nine arriving Japanese internees had syphilis, but there was no isolated infirmary in which to treat them.

The internees were

incarcerated until the end of the war. It wasn’t until 1948 that the

last ones — Germans — were released from a camp on Ellis Island. Even

then they were on probation for a year and prohibited from owning radios

and weapons.

Homes and businesses were

lost and families separated. Some of the former internees died as

paupers or returned empty-handed to their native countries.

Only the Japanese were given reparations: $20,000 each.

In 1988, Congress and

President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for how the Japanese had

been treated. Nothing, however, was said about Germans and Italians who

had suffered the same injustice.

More photos

Amelia Cotter - During

World War II, the U.S. established its largest prisoner of war (POW)

program in its history, with over 425,871 Axis prisoners being held by

May 1945.

Amelia Cotter - During

World War II, the U.S. established its largest prisoner of war (POW)

program in its history, with over 425,871 Axis prisoners being held by

May 1945.

In

Maryland, the POW camp program was initially developed in three

overlapping phases: planning for security and escape prevention, how to

benefit from the work of the POWS, and later, developing a program of

political rehabilitation.

Development of Maryland’s POW Program

In

the first stage, which lasted from December 1941 to the end of 1943,

the provost marshal’s office of the War Department, which was in charge

of the national POW program, established that one guard would need to

supervise every two or three prisoners. The office was largely concerned

with escape attempts and prisoners becoming hostile towards guards and

each other.

It was during this stage that the provost marshal’s

office established its Maryland installation at Fort George G. Meade,

located at the juncture of Anne Arundel, Howard, and Prince George’s

counties. Fort Meade received permission to start holding prisoners on

September 15, 1942, and initially held Axis-country civilians who were

trapped in the U.S. after the war erupted.

POW Camp at Fort George G. Meade

Starting

in September 1943 until July 1946, Fort Meade served as the main POW

camp in Maryland with a capacity of 1,680 prisoners. When it officially

began holding prisoners in 1943, Fort Meade held mostly Italians and a

few German POWs, until May 1944 when it officially became a German POW

camp. Most of the POWs captured and brought to Maryland were Wehrmacht

(army) personnel, though there were also some soldiers from the

Luftwaffe (air force) and the navy.

Around 1943, pressure began to

build on the War Department to loosen up some of its POW security

policies. Local farmers, businesses, and manufacturers—due to extreme

labor shortages—began to suggest that the POWs be allowed outside of

Fort Meade to work for them.

Maryland POWs as Local Laborers

As

a result, in June 1943 authorization was given to Fort Meade for

limited agricultural employment, but the War Department was unwilling to

allow the soldiers outside of the camp. Five months later, as

desperation for workers continued to grow, approval was given for the

establishment of new German POW camps in Maryland.

In February

1944, at a military-civilian conference held in Dallas, Texas, the War

Department formalized the change in its security policy and the

construction of 18 additional POW camps began. These camps would employ

workers in various agricultural and industrial activities in Maryland

under the terms of the Geneva Convention, which according to Richard E.

Holl in “Axis Prisoners of War in the Free State, 1943-1946,” stated

that “captured enemy officers could not be compelled to work and that

non-commissioned officers could only supervise," and that enlisted men

could work any job except one “demeaning, degrading, or directly related

to the war effort.”

According to Charles P. Wales—who served as a

guard at Camp Frederick in Frederick, Maryland from September 1945 to

spring 1946—in “P.W. Branch Camp #6: A Photo Essay,” many of the

prisoners who decided to work outside the camp were prompted by boredom.

By

August of 1945, over 4,000 POWs in Maryland were laboring for the army

or navy, and 6,000 for civilian contractors. Most prisoners worked

within the camps at camp bakeries, canteens, hospitals, or laundries.

Others dug ditches, built roads, and managed lawns. Farmers could apply

for extra prisoners through the Department of Agriculture’s War Food

Administration, while manufacturers had to go through the War Manpower

Commission to receive prisoner labor.

Benefits of POW Labor in Maryland

Not

only did the Maryland treasury benefit from POW labor, but prisoner

labor created a 35 percent increase in Maryland’s tomato crop in 1945

alone. A 40 percent increase in Maryland’s overall agricultural

productivity during the war years was also attributed to the work of

German POWs. From June to December 1945, German and Italian POWs in

Maryland saved the U.S government about five million dollars.

Kathy Kirkpatrick, Gentracer.org - The POW Camps in Maryland during World War II included:

•Edgewood Arsenal (Chemical Warfare Center), Gunpowder, Baltimore County, MD (base camp)

•Holabird Signal Depot, Baltimore, Baltimore County, MD (base camp)

•Hunt (Fort), Sheridan Point, Calvert County, MD (base camp)

•Meade (Fort George G.), near Odenton, Anne Arundel County, MD (base camp)

•Somerset (Camp), Westover, Somerset County, MD (base camp)

Enemy alien

internment camp:

•Howard (Fort), Baltimore County, MD (German, Italian)

•Meade (Fort George G.), near Odenton, Anne Arundel County, MD (held

German, Italian, Japanese and Misc. from June 1942 to December 1943)

Cemeteries:

•Fort George G. Meade Post Cemetery, Ft. Geo. G. Meade, MD, active military installation.

There were 5 base camps, 15 branch camps, 2 internment locations, and 1 cemetery in MD. More details in my latest book titled

Prisoner of War Camps Across America. It is available in Kindle format on

Amazon and in .epub and .mobi formats at the

GenTracer Shopping Cart.

This is the first of a five part series

that will be appearing on German Pulse over the next five weeks. Many

of the primary sources in this work come directly from the archives at

The Frederick County Historical Society in Frederick, Marlyand.

February 23, 2012

GermanPulse - During World War II, the United States

established its largest prisoner of war (POW) program in its history. By

May of 1945, over 425,871 Axis prisoners were being held in POW camps

across the country. Of these, 372,000 were German.

There were two POW camps located in Frederick County—both exclusively

holding Germans—Camp Ritchie and Camp Frederick. Camp Ritchie was

located in the northern part of the county and no more than 200

prisoners were held there at any given time, having little contact with

county residents. There is little information printed in the media about

that camp, but there are plenty of newspaper and magazine articles,

personal letters, and firsthand accounts concerning the men who lived

and worked at Camp Frederick, officially PW Branch Camp #6, which was

located just outside of the city.

It is known that prisoners at Camp Ritchie were mostly employed by

the military as carpenters, shoemakers, firemen, medics, orderlies, and

cooks. At Camp Frederick, prisoners were primarily employed in

agriculture, on privately owned farms, mostly as apple pickers. Some

were also contracted out to commercial companies, such as the Oxford

Fibre Brush Company, where they loaded and unloaded lumber. In essence,

the POWs performed the tasks that no one else could do, due to the

severe labor shortages as a result of the war.

This series of posts will focus primarily on the lives and

experiences of the men at Camp Frederick, and although the information

available is mostly one-sided, and most of the viewpoints are American,

the idea that Camp Frederick was not an unpleasant place for a POW to

be, and ran relatively smoothly with little unrest or injustice, is

accepted here. Perhaps not all German POWs across the Unites States had a

similar experience, but Camp Frederick truly appears to have been a

humane and relatively agreeable place for a POW to be held captive

during World War II.

The stories and experiences of both the prisoners and members of the

Frederick community are varied and surprising. It appears from their

descriptions that several of the POWs in Frederick left the country

having had a positive experience and even some good memories.

The citizens of Frederick felt undoubtedly afraid of and ambivalent

towards their enemy guests, but nevertheless, many of them found

friendship and even lifelong relationships with some of the prisoners.

Meticulously collected and continually revisited by the media over the

decades, the articles, letters, and firsthand accounts of the prisoners

and those that lived in Frederick reveal a very real, human, and

personal side of the war, in many cases breaking down both German

stereotypes and misconceptions about American nationalism.

Fort George G. Meade and the Maryland POW Camp System

In Maryland, the POW camp program was initially developed in three

overlapping phases: planning for security and escape prevention, how to

benefit from the work of the POWS, and developing a program of political

rehabilitation. In the first stage, which lasted from December 1941 to

the end of 1943, the provost marshal’s office of the War

Department—which was in charge of the national POW program—established

that one guard would need to supervise every two or three prisoners. The

office was largely concerned with escape attempts and prisoners

becoming hostile towards guards and each other. This explains why it

spent so much time deliberating on this phase and creating a tight

security policy.

It was during this stage that the provost marshal’s office of the War

Department established its Maryland installation at Fort George G.

Meade, located in the juncture of Anne Arundel, Howard, and Prince

George’s counties. Fort Meade received permission to start holding

prisoners on September 15, 1942, and initially held Axis-country

civilians who were trapped in the U.S. after the war erupted.

Starting in September 1943 to July 1946, Fort Meade served as the

main POW camp in Maryland with a capacity of 1,680 prisoners. When it

officially became a POW camp in 1943, Fort Meade held mostly Italians

and only a few German POWs, until May 1944 when it officially became a

German POW camp. Most of the POWs captured and brought to Maryland were

Wehrmacht (army) personnel, though there were also some soldiers from

the Luftwaffe (air force) and the navy.

Around 1943, pressure began to build on the War Department to loosen

up its harsh POW security policies. Local farmers, businesses, and

manufacturers—due to extreme labor shortages—began to suggest that the

POWs be allowed outside of Fort Meade to work for them.

As a result, in June 1943 authorization was given to Fort Meade for

limited agricultural employment, but the War Department was unwilling to

allow the soldiers outside of the camp. Five months later, as

desperation for workers continued to grow, approval was given for the

establishment of new German POW camps in Maryland. In February 1944, at a

military-civilian conference held in Dallas, Texas, the War Department

formalized the change in its security policy and the construction of 18

additional POW camps began.

These camps would employ workers in various agricultural and

industrial activities in Maryland under the terms of the Geneva

Convention, which stated that “captured enemy officers could not be

compelled to work and that non-commissioned officers could only

supervise.” Enlisted men could work any job except one “demeaning,

degrading, or directly related to the war effort.”

Not only did the Geneva Convention not allow forced labor, but

prisoners at Camp Frederick were considered Class A prisoners, meaning

all work was voluntary. According to Charles P. Wales, who served as a

guard at Camp Frederick from September 1945 to Spring 1946, many of the

prisoners who decided to work outside the camp were prompted by boredom.

By August of 1945, over 4,000 POWs in Maryland were laboring for the

army or navy, and 6,000 for civilian contractors. Most prisoners worked

within the camps at camp bakeries, canteens, hospitals, or laundries.

Others dug ditches, built roads, and managed lawns. Farmers could apply

for the extra prisoners through the Department of Agriculture’s War Food

Administration, while manufacturers had to go through the War Manpower

Commission to receive prisoner labor. In Frederick, the Frederick County

Agricultural Cooperative Association was formed in 1944 to “tap into

the pool of available prisoner labor.”

Read more from this 5 part series:

Part 1 (current) |

Part 2 |

Part 3 |

Part 4 |

Part 5

Related:

I have been posting this on numerous websites in hopes of getting

an answer. I work for a construction contractor at FT Meade MD. We have

been installing metro shelving units in a huge underground warehouse at

FT Meade.I was curious about the work for the selves are used to hold

bikes and the large doors we enter say FEMA. I always thought they did

something with hurricanes. We are almost done and now army officers are

loading the the shelves with bikes. So far I would guess that number at

10,000 - the selves when finished will hold close to 100,000 bikes. What do

they need with all these bikes. Another odd things - the different

sections are labeled with months starting with July 07. Anyone have any

idea what this means?