The Artificially Inflated Price of Food and Gas Can Be Blamed on the Commodities Futures Modernization Act of 2000

According to a 2009 article about the exemption for Goldman Sachs:

There was a 1936 government regulation which had successfully stopped this type of shenanigan. In effect it did not allow large speculators to lean on any commodity market and crowd out real producers and consumers. Until 1991. That’s when Goldman Sachs’ commodities subsidiary, J. Aron, requested an exemption based on the flimsiest justification. Amazingly enough it got it. And over the years the CFTC handed out 14 other similar exemptions. Goldman and its ilk were busy with a few other schemes and it wasn’t for a while that they started to really take advantage of the loophole they had gained. What followed was nothing short of astonishing. For example: Between 2003 and 2008, the amount of speculative money in commodities grew from $13 billion to $317 billion, an increase of 2,300 percent.Brooksley Born, the head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission [CFTC] under Clinton, warned about how the the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 could potentially cause the type of meltdown we had in 2008. She was opposed by Greenspan, Rubin and Summers, who eventually convinced Congress to not heed her warnings about the danger of unregulated derivative markets. The episode of the PBS series FRONTLINE titled "The Warning" is an excellent account of this period.

Click on the ("more") link on the web page to read the rest of the story before watching:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/warning/view/#morelink

"It'll happen again if we don't take the appropriate steps," Born warns. "There will be significant financial downturns and disasters attributed to this regulatory gap over and over until we learn from experience."

Residential real estate may be slumping, but ag land is booming. In Iowa, farmland prices have never been higher, having increased a whopping 34 percent in the past year, according to The Des Moines Register. The boom is driven in part by agribusiness expansion, but also by a new player in the agriculture game: private investment firms. Both are bidding up land values for the same reason: the price of food.

They're betting on hunger, and their reasoning, unfortunately, is sound. This is bad news for would-be small farmers who can't afford land, and much worse news for the world's hungriest people, who already spend 80 percent of their income on food.

Thanks to the world's growing population of eaters and the fixed amount of land suitable for growing food to feed them, supply and demand tilts the long term forecast toward higher prices. More immediate concerns -- like increasing demand for grain-intensive meat and the rise of the corn-hungry ethanol industry -- have fanned the flames of a speculative run-up in agricultural commodities like corn, wheat, and soy. Add cheap money to the mix in the form of low interest rates, along with an army of traders chasing the next bubble, and you've got a bidding war waiting to happen.

The Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 allowed the bidding to begin by allowing the trade of food commodities without limits, disclosure requirements, or regulatory oversight.

The Act also permitted derivatives contracts whereby neither party was hedging against a pre-existing risk; i.e. where both buyer and seller were speculating on paper, and neither party had any intention of ever physically acquiring the commodity in question.

Agricultural commodities markets were created so that traders of food could hedge their positions against big swings in prices. If you're sitting on a warehouse full of corn, it's worth making a significant bet that the price will go down, just in case it does, and makes your corn worthless. That way at least you make money on the bet. Derivatives can add leverage to your bet, so you don't need to bet the entire value of your corn in order to protect it.

Derivatives, it turns out, are also really cool if you want to make a ton of money by betting just a little. And if you can bet a lot, even better, as long as you keep winning. The golden years of commodities trading lasted from 2002 to 2008, when prices moved steadily, but not manically, upward. Then they crashed. And then they rose even higher than before. This is the kind of volatility, except worse, that commodities trading was created to prevent.

UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Olivier De Schutter recently released a "Briefing Note" titled, "Food Commodities Speculation and Food Price Crises."

As he sees it, "Beginning at the end of 2001, food commodities derivatives markets, and commodities indexes in particular, began to see an influx of non-traditional investors, such as pension funds, hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and large banks. The reason for this was simply because other markets dried up one by one: the dotcoms vanished at the end of 2001, the stock market soon after, and the U.S. housing market in August 2007. As each bubble burst, these large institutional investors moved into other markets, each traditionally considered more stable than the last."

In those years, the market value of agriculture commodities derivatives grew from three quarters of a trillion in 2002 to more than $7.5 trillion in 2007, while the percentage of speculators among agriculture commodities traders grew from 15 to 60 percent. The total number of commodities derivatives traded globally increased more than five-fold between 2002 and 2008.

The rush of speculators into agricultural commodities created something like a virtual food grab. While a traditional speculator might drive up the price of a commodity by physically hoarding it, now speculators, fund managers, sovereign nations, and anyone else with the money can do the same by hoarding futures contracts for food commodities, but with no expectation that they will have to physically deal with actual commodities. No messing with deliveries, maintaining warehouses, trapping mice, or other reality-based headache unless they happen to truly want the commodity.

Americans may not be starving, but we are feeling the pinch, paying upwards of a dollar for an ear of sweet corn at farmers markets, while in the southwest, dried corn chicos, a local delicacy, have doubled in price. In D.C., a group of livestock producers addressed the House Agriculture Committee last week, seeking the elimination of federal mandates for ethanol use in gasoline. The meat makers blame high corn prices on the biofuels industry.

If this was just about corn, I would say let the cows and cars fight over it. They can have it. After all, whatever corn doesn't get converted to chicken feed and gasoline probably isn't going to be made into chicos anyway. It's going to be made into corn syrup for the young and the obese.

But the commodities markets of the world are connected, running together in a herd, which makes this about a lot more than corn. It is likely that increased demand for meat and the rise of ethanol were indeed a trigger in rising corn prices, De Schutter says, dragging the rest of the grain markets into the bubble. But it was deregulation that opened the doors to betting on hunger.

A logical place to start calming food prices would be to un-deregulate them. And there's hope of that happening. The United States, by far the biggest player on the commodities stage, just made a step in that direction with the passage of the recent Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act. The Act puts size limits on individual holdings, including agriculture commodities and derivatives.

Unfortunately, given the global nature of capital, even if the U.S. were to completely shut down speculation, it would just move offshore. International regulation is what's needed, and since the U.S. opened this Pandora's box of speculative horrors with deregulation, we have the moral responsibility, not to mention the political firepower, to shut it.

With financial regulators underfunded and understandably distracted, a strong show of public support could help get their attention. But if our biggest inconvenience is higher prices for meat and sweet corn, that public display might be hard to come by. Especially if our retirement portfolio, wisely diversified with commodity index funds and ag land holdings from Iowa to Ethiopia, is growing.

Phil Gramm's Part in the Global Financial Collapse [Excerpt]

The alternative press leads on the policy roots of the credit crisisColumbia Journalism Review

Phil Gramm [who served as a Democratic Congressman (1978–1983), a Republican Congressman (1983–1985) and a Republican Senator from Texas (1985–2002)] threw his weight behind the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which, among other things, paved the way for a boom in those nasty credit default swaps that are coming back to haunt us all. Writes Galbraith:

This, combined with other deregulatory moves by the CFTC [Commodity Futures Trading Commission], broadened the ‘swaps loophole,’ an enormous backdoor into the commodities markets, basically permitting speculators making bets off the commodities exchanges to be treated as ‘commercial interests’—like say, farmers—and hence avoid the scrutiny (including limits on the size of their bets) normally applied to financial players.And, as is better known, Gramm also co-sponsored 1999 legislation—backed by the Clinton Administration—[the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which repealed portions of the Glass-Steagall Act] that collapsed the distinction between investment and commercial banks.

In the interest of credit where credit is due, we note that Mother Jones, while notable for its force and persistence, was not the first publication to have looked closely at Gramm’s history. Credit also goes to The Texas Observer, where a rigorous article by Patricia Kilday Hart, from last May, pinpoints Gramm as an architect of the financial crisis.

Here is Hart on the circumstances of the 2000 legislation:

In the early evening of Friday, December 15, 2000, with Christmas break only hours away, the U.S. Senate rushed to pass an essential, 11,000-page government reauthorization bill. In what one legal textbook would later call ‘a stunning departure from normal legislative practice,’ the Senate tacked on a complex, 262-page amendment at the urging of Texas Sen. Phil Gramm.

There was little debate on the floor. According to the Congressional Record, Gramm promised that the amendment—also known as the Commodity Futures Modernization Act—along with other landmark legislation he had authored, would usher in a new era for the U.S. financial services industry.

Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000

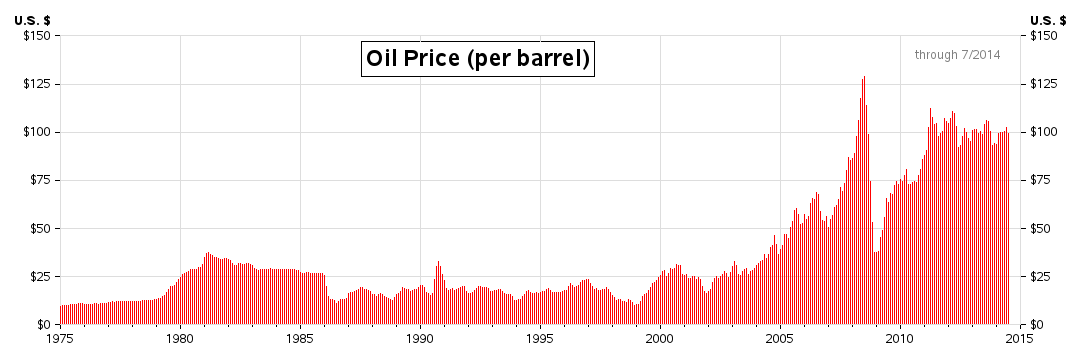

We may never know for sure the combination of circumstances that brought on energy crisis of 2008. But one factor was almost certainly the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000, which allowed unprecedented levels of speculation in oil futures by investment banks and pension funds, bringing the familiar boom-bust cycle home to the gas pump. [Drill Now? Try Regulate Now., Wall Street Journal, April 7, 2010]To lower international food prices and protect our social interests, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission must use its authority to curb excessive speculation in commodities futures and re-establish strict position limits on speculators (which were successful until removed by the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000). We must regulate and bring transparency to all trading. We can also removing damaging speculative influence on commodities prices by prohibiting participation in commodities markets by those who do not produce, manufacture, or take physical delivery of the commodities. We must create a solidarity economy that puts compassion and care for one another ahead of short-term profits, in the United States and around the world. [The world food crisis: what is behind it and what we can do, WorldHunger.org, October 23, 2008]

The surge in world food prices can be attributed to the “financialisation” of commodities due to the Commodities Futures Modernization Act of 2000. The game changed for commodities the minute the legislation passed. That doesn't explain the surge this year but it does explain the increased volatility of the last decade. [Don't Blame Bernanke: Here's Who's REALLY To Blame For Surging Food Prices, Business Insider, October 12, 2010]

And what caused the huge spike in oil prices? Take a wild guess. Obviously Goldman had help — there were other players in the physical-commodities market — but the root cause had almost everything to do with the behavior of a few powerful actors determined to turn the once-solid market into a speculative casino. Goldman did it by persuading pension funds and other large institutional investors to invest in oil futures — agreeing to buy oil at a certain price on a fixed date. The push transformed oil from a physical commodity, rigidly subject to supply and demand, into something to bet on, like a stock. Between 2003 and 2008, the amount of speculative money in commodities grew from $13 billion to $317 billion, an increase of 2,300 percent. By 2008, a barrel of oil was traded 27 times, on average, before it was actually delivered and consumed. [Matt Taibbi, The Great American Bubble Machine, Rolling Stone, July 2, 2009]

The price of crude oil today is not made according to any traditional relation of supply to demand. It’s controlled by an elaborate financial market system as well as by the four major Anglo-American oil companies. As much as 60% of today’s crude oil price is pure speculation driven by large trader banks and hedge funds. It has nothing to do with the convenient myths of Peak Oil. It has to do with control of oil and its price. [F. William Engdahl, ‘Perhaps 60% of today’s oil price is pure speculation’, Global Research, May 2, 2008]

Related:

This 2011 report was prepared for the CT General Assembly:

http://www.cga.ct.gov/2011/rpt/2011-R-0290.htm

This one summarizes Goldman's history in the commodity markets:

http://articles.marketwatch.com/2009-07-28/industries/30703972_1_commodity-index-position-limits-index-traders

And here's the smoking gun: the CFTC's 1991 letter to the Goldman subsidiary. GS was applying for an exemption as a bona fide hedger instead of a speculator:

http://www.marketwatch.com/_newsimages/pdf/j-aron-letter-20090727.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment