Cops are Trained to Shoot "Center Mass" to "Stop the Threat," Which Means to Shoot to Kill

We need to acknowledge and address the problems of LEOs whose use of deadly force is not justified by the urgency of a situation. It is time for the police community to admit that they have some problem officers in their midst and help find a way to deal with them too. A civilized society does need some sort of law enforcement but it must be part of the society and not apart from it (or from significant parts of it.)

A 12-month study by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 1.4% of people who had contact with the police had force used or threatened to be used against them.

Police officers are trained to quickly assess possible threats. Force, particularly deadly force, may be used if officers can explain their perception of the physical threats that put them and/or others at substantial risk of serious bodily injury or death. Departmental policies and police training in the United States reflect the "objective reasonableness" principle put forth in the U.S. Supreme Court's 1989 Graham v. Connor decision, which applies a three-part test to assess the seriousness of the offense, the suspect threat, and the suspect's resistance or evasiveness.

"Officers are trained to shoot until the threat is no longer presenting a threat," says David Klinger, a former police officer who shot and killed a man while a police officer in Los Angeles in 1981 (he fired one fatal shot that killed a man who had stabbed a fellow officer with a butcher knife). "It's not unusual for police officers to find themselves in a circumstance where they have to shoot multiple rounds because the suspect simply isn't stopping," Klinger says. Klinger, now an associate professor in criminology and criminal justice at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, says it also is important that officers have non-lethal means available to quell a violent suspect, including a Taser. Officers are trained to gauge the threat and use reasonable force, all in a time frame of a few seconds or less. Klinger says cultural differences can dictate how people react to police trying to stop them — from walking in the middle of the street, for example — especially if they have long felt persecuted by law enforcement. Police should be trained in these realities, especially if the lens through which (some people) see the world is one where police are constantly doing this because of the color of my skin or because of the economic status of my life. This training can help police tailor their actions in less confrontational ways, perhaps preventing events from spinning out of control, says Jim Bueermann, president of the Police Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based non-profit organization that conducts research and training to improve policing. "Under this idea, you allow people to interact before you use the authority that the law has invested in you," he says. "Training in these kinds of issues is, I think, lacking in the United States." [Source]

"I served 11 1/2 years with the VIPD and never shot anyone. I am only 5'6" and disarmed many a foe without firing a shot. In my day, if you killed anyone you were charged just like any other criminal, so you had that on your mind every time you responded to a call. You were taught self defense, including karate and boxing. I trained privately and earned a first degree black belt. I believe the proliferation in killings has to do with the training and the emphasis on the use of the weapon. We were given a baton, a black jack and handcuffs, which you could use before using deadly force. I don't think that the average officer understands what it is to be criminally charged and that is why they are so eager to use deadly force. The stress that you face when you are charged is worse than having a tooth ache. Also, the culture of the higher-up to condone and cover-up for the rank and file does the profession a disservice and puts the officers at more risk. The culture and training must change as we are living in an audio-video world. Big Brother is everywhere. - Augustin, Yahoo!, June 12, 2015

Comments from Shooter's Forum on the thread "Are police trained to shoot to kill?":

Yes, they are trained to shoot to kill now! Years ago they could bounce a bullet off the ground to wound some one if they wanted to do that, but not now! Only on TV do they shoot the gun out of some ones hand! Center of mass is a killing shot!

Talked with a soon to be retired officer....the general response was, "We were trained to shoot to stop...having them die was just a bonus."

Police Academy instructors say over and over, "shoot to STOP." Defense attorney's would love to hear "shoot to KILL."

When I was a Weapons Training Instructor with a very large non-Federal department, we taught to "shoot to stop the threat," and "don't stop shooting until the threat is over." Any bad guy worth shooting once, is worth shooting twice.

The way it was explained to me, the ONLY reason in Arizona for legally shooting someone is to stop the threat. To shoot to stop the threat, one must shoot intending to kill. A live BG can still shoot or hurt you or others. However, if the threat ends while the BG is still alive, you've accomplished your intentions without killing him. No more shooting. Therein lies the difference, if you think about it. If a person were to shoot to kill, they'd keep shooting until the perp was dead. If you shoot to end the threat, and the threat stops while the BG is still alive, you've accomplished your goal. If the bad guy dies, you've also accomplished your goal. So, you shoot only to end the threat. Make sense?

When deadly force is justified, shooting to stop is still the practice. Obviously, the application of deadly force can and does resort in death, but death is not the desired result, at least not under oath!

I was taught to shoot to stop. It is the crook's problem if he dies. We signed a document when hired indicating we knew we might have to stop someone during our career. I will shoot according to policy and procedures established by the department and worry about the rest later. I may be saving another officer's life or the general public. Not, however, just for the sake of property. Clear as mud? Maybe. After a shooting most departments give you admin. leave and mandatory time with the nice psychologist.

I was taught to shoot two, minimum, to center mass. If you have determined shooting is necessary you have already determined that killing is justified. We did not shoot, non-violent wanted offenders; we were authorized to shoot wanted violent offenders to prevent their getting away. Warning shots are not allowed.

Law Enforcement in Washington State are trained to stop the threat. Center of mass when available or anywhere else until the threat is over. Unfortunately, death sometimes occurs.

All officers are taught to shoot for (Center Mass) because this helps to alleviate the chance of an inocent bystander being injured. It also eliminates the chance of the perp shooting an inocent bystander, by stopping the confrontation as quickly as possible. Shooting the gun out of the hand of the bad guy only happens in the Movies. The ,ain duty of the police officer is to preserve life, not to endanger others in the preformance of his duty. As in the previous post, unfortunately, death sometimes results. This is not a desired objective, but is a fact of life.

Isn't center mass called that because, statistically, it is most likely the place to get a kill shot since it hits the majority of vital organs? I realize that few want to kill anyone, but guns when used imply lethal/deadly force. So this statement that police are trained to stop the threat, if you aim center mass isn't that because you intend to stop him for good, or am I mistaken in that center mass is intended to be fatal? My question is, based on an assault placed on a Police Officer, say some one runs at him/her with knife gun or just in a manner of assault? Do they shoot to kill?

Just a PC language difference...they are trained to shoot to stop...it's just with current technology, "stopping" and "killing" are about the same thing. High center of mass simply because it gives you the most error for a telling hit...a little left or tight, up or down, and you still connect with something vital. Just so happens that those vital areas that produce stopping also tend to produce death. Any drastic rapid drop in blood pressure, and you drop like a sack of doorknobs...center of mass happens to be the high pressure center of circulation, so a hole in any of the major pipes there usually shuts the system down. So the way it's designed, a police officer can say he shot to stop...the death of the suspect was an unintended consequence of needing to stop him.

Actually it's 2 in chest and 1 in neck or head. That drill is to defeat ballistic vests. The LA bank robbery taught us that. Now it also includes one on each side of the pelvis to create massive shock to stop the threat. Center of mass does several things: first, it gives the shooter a large target to hit in a high stress situation; second, the sudden dump of energy from the hollow point will create massive shock; and, third, there hopefully will be enough mass to stop the bullet from over-penetrating and hitting a bystander behind the suspect that was not seen. I've been doing this job for 20 years. I got a whole lot of years left. I will use my weapon if called upon. I hope that never happens. My biggest fear is not hitting the suspect but rather accidentally hitting an innocent person nearby. I have to tell you that I hope to never have to discharge my weapon at someone. I've come very close several times. The aftermath of what the officer, his/her family, as well as the family of the suspect is horrible. Officers will be dragged through the mud in the press and in court. God forbid if the suspect was African American and the officer white. Anyone who thinks they want to get into a shooting better look at the statistics on those that have. Most don't make it two years into their carreer. The majority, if married, get divorced. Psychological, "what if" will haunt you for the rest of your life.

Officers are trained to stop. If the actor dies, well, tough. This carries over into self defense as well. Always shoot to stop an action. Sometimes deadly force leads to death, but that is strictly a by-product.

Most Departments do not allow shooting to scare (warning shots). This is a bad practice, as you are putting bystanders in danger from your shot possibly not having a backstop.

It seems to me if they shot to stop a threat and the person lives, there is a huge lawsuit there also.

I'd rather face 12 jurors in a lawsuit and tell them it was my intent to stop the threat and not my intent to kill. (This would be true, by the way, if it ever happens.) The idea to draw your weapon with the intent to kill places ourselves as the prosecutor, judge, jury and executioner. I'm sworn to uphold the law, not punish people for breaking it.

Chicago charges officer in black teen's death, releases video of shooting

November 24, 2015

Reuters - A white Chicago policeman who shot a black teenager to death was charged with murder on Tuesday in a prosecution hastened in hopes of averting renewed racial turmoil over the use of lethal police force that has shaken the United States for more than a year.

A highly anticipated video of the 2014 shooting, taken from a camera mounted on the dashboard of a police squad car, was released under orders from a judge hours after the officer in question, Jason Van Dyke, made his first appearance in court.

Amid intense interest from the media and public, the police department website where the footage was posted became overwhelmed and initially crashed.

The city braced for demonstrations but so far only a group of about 100 people were protesting about a mile south of Chicago's business district.

The video clip showed 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, who authorities said was carrying a knife and had the hallucinogenic drug PCP in his system, as he was gunned down in the middle of a street on Oct. 20, 2014, as walked away from officers who confronted him.

Prosecutors said he was shot 16 times by Van Dyke, who emptied his gun and was preparing to reload his weapon. Van Dyke has said through his lawyer and the police union that the shooting was justified because he felt threatened by McDonald.

"Clearly, this officer went overboard and he abused his authority, and I don't think use of force was necessary," top Cook County prosecutor Anita Alvarez said at a news conference after Van Dyke's initial hearing.Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel appealed for calm as the city prepared for possible protests.

"It is fine to be passionate but it essential to remain peaceful," Emanuel told a news conference to announce the release of the video.Emanuel was flanked by a dozen community leaders.

At the same news conference, Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy said police would "facilitate" protests but would not tolerate criminal behavior.

Van Dyke was denied bail at a hearing in Chicago's main criminal courthouse hours after prosecutor Alvarez announced charges of first-degree murder. If convicted, Van Dyke could face 20 years to life in prison.

At the brief court hearing, Cook County Circuit Court Associate Judge Donald Panarese scheduled a second hearing for Monday where he said he wanted to view the video in court and reconsider bail for Van Dyke based on its content. Prosecutor Bill Delaney told the judge that witnesses and the video concur that McDonald was not moving toward Van Dyke.

MISCONDUCT

Van Dyke has had 20 misconduct complaints made against him during the past 4-1/2 years, none of which led to any discipline from the Chicago Police Department, according to research by Craig Futterman, a University of Chicago law professor and expert on police accountability issues.

"The Chicago Police Department refuses to look at potential patterns of misconduct complaints when investigating police misconduct," Futterman said. "If the department did look at these patterns when investigating police abuse, there is a great chance right now that 17-year-old boy would still be alive."

"With release of this video it's really important for public safety that the citizens of Chicago know that this officer is being held responsible for his actions," she said.Last week, a court ordered the release of the video. The police union objects to its release.

McDonald's death came at a time of intense national debate over police use of deadly force, especially against minorities. A number of U.S. cities have seen protests over police violence in the past 18 months, some of them fueled by video of the deaths.

The uproar was a factor in the rise of the Black Lives Matter civil rights movement and has become an issue in the 2016 U.S. presidential election campaign.

Van Dyke's lawyer Daniel Herbert said his client would prevail in court.

"This is a case that can't be tried in the streets, it can't be tried in the media, and it can't be tried on Facebook," Herbert said.FAMILY CALLS FOR CALM

McDonald's family called for calm, as did city authorities and black community leaders.

"No one understands the anger more than us, but if you choose to speak out, we urge you to be peaceful. Don't resort to violence in Laquan's name. Let his legacy be better than that," McDonald's family said in a statement through their lawyer.In Baltimore and Ferguson, Missouri, family appeals for peace were not always heeded.

Black community leaders in Chicago said they feared violent protests in reaction to the video. Politicians and church leaders in the Austin neighborhood urged potential demonstrators to protest peacefully.

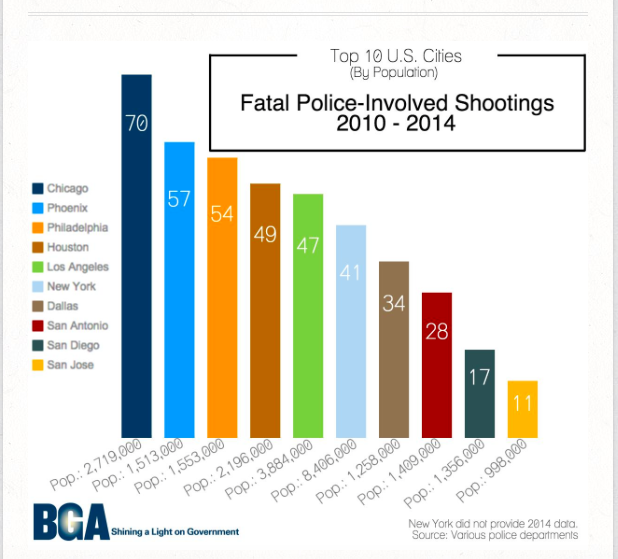

"We feel your pain, but we challenge you to turn your pain into power. We know protests are coming, please allow them to be peaceable," the Rev. Ira Acree said at a news conference.Police shootings are frequent in Chicago, the third-largest city in the United States with 2.7 million people, roughly one-third white, one-third black and one-third Hispanic.

From 2008-2014 there were an average of 17 fatal shootings by police each year, according to data from the Independent Police Review Authority, which investigates police misconduct.

Almost all shootings, fatal and non-fatal, are found to be justified.

What Police Said About The Killing Of Laquan McDonald Before The Video Showed What Really Happened

Think Progress - 17-year-old Laquan McDonald was shot dead by officer Jason Van Dyke on October 20, 2014. Here is how the police union described the shooting to the Chicago Tribune for an article published on October 21:

“He’s got a 100-yard stare. He’s staring blankly,” [Fraternal Order of Police spokesman Pat] Camden said of the teen. “[He] walked up to a car and stabbed the tire of the car and kept walking.”

Officers remained in their car and followed McDonald as he walked south on Pulaski Road. More officers arrived and police tried to box the teen in with two squad cars, Camden said.

McDonald punctured one of the squad car’s front passenger-side tires and damaged the front windshield, police and Camden said.

Officers got out of their car and began approaching McDonald, again telling him to drop the knife, Camden said. The boy allegedly lunged at police, and one of the officers opened fire.

McDonald was shot in the chest and taken to Mount Sinai Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 10:42 p.m.The Chicago police have had video of the shooting for a year, but refused release it until ordered to do so by a judge.

On Tuesday, the video finally released, and Van Dyke was charged with murder.

The video directly contradicts the account provided to the press after McDonald’s death. McDonald does not “lunge” at the police or do anything threatening. It also shows Van Dyke firing repeatedly at McDonald after he is on the ground and motionless.

In April, police officer Michael Thomas Slager was charged with the murder of Walter Scott after a video contradicted the official police account.

Many police shootings are not captured on video, however. The prosecution of police officers for murder is extremely rare.

Shooting to kill: Why police are trained to fire fatal shots

January 6, 2015CLEVELAND.com - After the shooting death of a 12-year-old Cleveland boy at the hands of a police officer came the familiar question: Why did they have to kill him? Why didn't they shoot the gun out of his hand or shoot him in the leg?

Police responded with the familiar refrain: We don't shoot to maim. If there is a threat that requires lethal force, we shoot to kill.

But where did that policy come from? In this age of sophisticated weaponry and training techniques, can officers be trained to shoot suspects in a less deadly way?

Some officers are able to do this. Just six days after Tamir was killed, a seven-year veteran police officer in Akron shot a man in the leg who was holding knives to a woman's throat.

Police officers who come face-to-face with armed and dangerous suspects are trained to "shoot to kill," but experts say that phrase doesn't account for the complexities of an officer-involved shooting.

As the Cleveland community grapples with questions about whether the police shooting of 12-year-old Tamir Rice was justified, the U.S. Department of Justice's report on the Cleveland Division of Police uncovered a history of failures within the department - especially in how officers use deadly force.

Justice officials found cases where Cleveland police shot at people who were following their orders and even victims of a crime who were fleeing from danger.

Though not a part of the Justice Department's investigation, the Tamir Rice shooting is indicative of Cleveland officers' habit of turning to deadly force as an initial response rather than a last resort.

But when Officer Timothy Loehmann fired twice at Tamir's stomach, he was following long-established deadly force protocol that would justify the shooting if the boy posed a life-threatening risk.

Northeast Ohio Media Group asked law enforcement experts and researchers to shed light on why officers target vital organs when they fire their weapons, rather than attempting non-lethal shots.

Going for the "kill zone"

Asked whether police officer training historically teaches a "shoot to kill" philosophy, veteran officers overwhelmingly answered "yes," but said death isn't necessarily the end goal.

"Killing isn't the objective," said Geoffrey Alpert, professor at University of South Carolina who researches high-risk police activity. "The objective is to remove the threat."The most effective way to do that is to shoot at a person's torso because it's the largest part of the body – and where a shot is most likely to incapacitate someone who poses a potential threat, Joseph Morbitzer, president of the Ohio Association of Chiefs of Police said.

Officers train during target practice by firing at paper targets shaped like people where the bullseye is the chest near the sternum, according to Thomas Aveni, executive director at the Police Policy Studies Council.

Shooting to wound is a myth

Officers who shoot at a suspect's upper body are often condemned by the public for not aiming at an arm or leg instead, but experts say that only happens in Hollywood.

"You're shooting something that's moving and turning, and people don't make themselves an easy target," Aveni said."Those that advocate shooting a gun out of a hand like you see in Roy Rogers movies – that's just not a plausible scenario."Hubert Williams, 30-year veteran officer and former president of the Police Foundation, said the philosophy is to shoot to kill or not at all.

"[An officer] wouldn't be justified in shooting unless there is a threat to his life," Williams said. "If there's a threat to his life, he has to take counter measures against that threat. So he's going to shoot not to stop him – he's going to shoot for the kill zone."The law takes into account the difficulties faced by officers confronting an armed person.

Police are justified in shooting someone who they believe poses a life-threatening risk, but perception of danger is a difficult thing to legislate, according to Michael Benza, criminal law professor at Case Western Reserve University.

"Its not one of those things that we can give officers guidelines for," Benza said. "We recognize that they can sometimes shoot innocent people because they misinterpret the situation."

Still, he agrees that shooting to kill is the only plausible method for self-defense.

"Nobody who is trained in defending themselves or firearms is taught to shoot to wound," Benza said.Shaping deadly force protocol

Crime waves in Chicago and New York shaped how police used guns in the last 150 or so years.

Police began arming themselves with guns in the mid-19th century, according to Thomas Reppetto former commander of detectives in the Chicago Police Department. Reppetto also served as the president of the Citizens Crime Commission in New York City and has written extensively on police and the American Mafia.

It wasn't until Theodore Roosevelt took office at the close of the 19th century that gun use became standardized. Roosevelt equipped the NYPD with revolvers and mandated target practice.

Police amped up their armory again in the 1920s in response to Chicago Mafia crime, which included machine gun attacks.

Repetto said police lore in New York and Chicago in the Prohibition Era was to avoid pulling a gun on duty. In the crowded urban areas, police limited their gun use to avoid accidentally shooting bystanders.

Reppetto said even though there were far fewer police shootings then, there was still public outcry over officers using deadly force.

The next big change came during the drug wars of the late '80s and early '90s, when the NYPD got 9-millimeter automatic pistols to replace their six-shot revolvers to keep pace with well-armed gangs.

Guns on trial

Deadly force policy has been altered in the past 30 years by three landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases.

A 1985 case nixed policies that permitted officers to shoot a suspect just because they are fleeing. The court ruled that a person has to be posing an immediate threat of serious physical harm in order for police to justifiably shoot them.

In 1989, the court said officers can use deadly force if it is proven to be reasonable based on the unique circumstances of a situation.

A 1994 case ruled that police are not required to use less lethal force (like pepper spray or a Taser) before resorting to deadly force (a gun) if there is a threat to someone's life.

No signs of change

It's very unlikely the shoot-to-kill policy will ever change, according to Terrry Dwyer, retired policeman and legal columnist for PoliceOne.com, an online police procedure resource.

Shooting at center mass is a long-standing police protocol that has the law on its side, Dwyer said.

In 2010, lawmakers in New York tried and failed to push a "minimum force" bill through the state assembly, which would require officers to shoot at suspects only to wound them.

While Dwyer said the sheer practicality of deadly force protocol has helped it withstand opposition over the years, legislators and activists are reviewing the ways officers use it.

Ohio Attorney General Mike DeWine set a meeting for Thursday with the Ohio Peace Officer Training Commission, which sets standards for officer training across the state, to review deadly force training.

In light of Tamir's death and the Justice Department's criticisms, DeWine wants to make sure police academies are doing everything they can to ease tension between police and the communities they serve.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Ohio is also working on use of force policy recommendations for the Justice Department as it works to reform the division.

"The report was very vivid in depicting a police force that used force excessively - all types of force, not just deadly," said Mike Brickner, senior policy director for ACLU of Ohio. "This has been a historical problem in Cleveland and once we very much need to address," he said.

US police should shoot to kill or not at all, law and justice experts say

August 21, 2014The Guardian - In the wake of a second fatal police shooting in the St Louis area after the death of Michael Brown, concerned citizens are asking why officers had to kill Kajieme Powell, a 25-year-old man who was holding a knife and “behaving erratically.”

They want to know why officers don’t shoot someone like Powell in the leg or the arm, rather than aiming for vital organs, or why they don’t just use a less lethal weapon, like a Taser.

Experts say “shooting to wound” only works in movies. In reality, it doesn’t make sense legally or tactically. And, they say, less-lethal force isn’t always appropriate in certain circumstances, especially when a suspect is wielding a weapon at a close range. Here’s why.

Why not shoot for the arm or leg?

Police officers in the US are trained to shoot to kill, not incapacitate.

Shooting a suspect in the arm or the leg would be difficult for John Wayne, never mind the most skilled marksman on the force, said Candace McCoy, a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York.

If a police officer decides to fire, and is justified in doing so, they will be shooting under intense pressure at a dangerous suspect who is likely moving quickly, all of which makes it incredibly difficult to hit a target, McCoy said. Officers are trained to shoot at “center mass”, roughly the chest region, because they’re more likely to hit the target and stop an imminent threat.

McCoy said the legal threshold for using deadly force is high: an officer can only shoot at a suspect who poses a life-threatening risk to the officer or the public. She said allowing officers to “shoot to wound” would lower that threshold.

“As a policy, [shoot to wound] is a really bad idea because it would give the police permission to take that gun out of the holster under any circumstance,” she said.A shoot to wound policy could lead to more unintentional police killings by expanding the range of circumstances in which an officer would be allowed to use his or her weapon.

Lawmakers have in the past attempted to introduce so called “minimum force” measures that would require officers to shoot a dangerous suspect in the arm or leg. Such legislation is strongly opposed by law enforcement groups.

Why not use Tasers instead of guns?

It’s a surprisingly simple answer: as David Klinger, an associate professor in the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Missouri–St Louis and a former officer with the Los Angeles police department, says, “Officers aren’t required to risk their lives unnecessarily.”

Officers are trained to use deadly force on suspects wielding weapons, Klinger said. He added that if an officer is confident enough, he or she can try to incapacitate the suspect with a less-than-lethal device, but if that fails, the officer would have to use a gun anyway, and by then it could be too late to stop them, and their own lives – or the lives of other civilians – would be at risk.

Based on video of the Powell shooting released by St Louis police, Klinger said Powell left the two officers with no choice but shoot because he advanced at them brandishing a knife.

“It’s tragic and its unfortunate, but the suspect here in this situation drove the encounter,” Klinger said. “He really didn’t give the officers many options.”Police do have options in other situations. Uniformed officers typically carry at least one less-lethal option in their duty belts, including, among other things, batons, pepper spray, Tasers or rubber bullets, Klinger said.

William Terrill, a professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University, said there is a continuum that dictates use of force by police officers. He said the amount of force officers use should be proportional to the threat posed. The spectrum scales from using verbal force to firing a gun.

While US law is clear on when deadly force can be used, Terrill said it’s very difficult to legislate the use of less-lethal force.

“The law simply says, the force has to be objectively reasonable,” he said. “What does that mean, objectively reasonable? That’s very hard for an individual officer to figure out.”As US police departments increasingly adopt less-than-lethal devices, Terrill said there needs to be a more standardized approach to training officers to use them.

Given the gap in the law, it comes down to departments to regulate the use of less-lethal force, and that leads to some major disparities.

“We’re kind of the wild west when it comes to less-lethal force policy,” he said.

Why Do Cops So Often Shoot To Kill? [Excerpt]

Huffington Post - Members of law enforcement are legally permitted to use deadly force when they have probable cause to believe that a suspect poses a threat of serious physical harm either to the officer or to others. In such cases, most officers are trained to shoot at a target's center mass, where there is a higher concentration of vital areas and major blood vessels, according to a report by the Force Science Institute, a research center that examines deadly force encounters.

John Firman, director of research, programs, and professional services at the International Association of Chiefs of Police, said that shooting at a limb is impractical. Aiming at an arms or legs, which move fast, could result in a misfire that fails to neutralize the threat and may even hit the wrong person, he said. "The likelihood of success is low."

"That's a Hollywood myth," Firman told The Huffington Post when asked why police officers don't tend to shoot people in the limbs. "In all policy everywhere on force in any law enforcement agency in America, the bottom line statement should read: If you feel sufficiently threatened or if lives are threatened and you feel the need that you must use lethal force, then you must take out the suspect."Officers are trained to assess the risk before firing, Firman said, but often a situation escalates quickly. A guide from his association on officer-involved shootings states that deadly force is legally justified "to protect the officer or others from what is reasonably believed to be a threat of death or serious bodily harm; and to prevent the escape of a fleeing violent felon who the officer has probable cause to believe will pose a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others."

The legal justification for deadly force by police is informed by the 1985 Supreme Court ruling in Tennessee v. Garner, in which a pair of police officers fatally shot a 15-year-old boy after he fled from a burglary. It turned out the boy had stolen a purse and just $10 from a house, and the Court ruled that a police officer may only use deadly force to prevent the escape of a violent felon.

Some law enforcement officials said the question of whether officers should shoot to wound or kill misses the point. Officers are often forced to make a split-second decision and are trained to try and deescalate the situation before firing.

What are rules of engagement?

Lt. Col. David Bolgiano, U.S. Air ForceAuthor, Combat Self-Defense: Saving America's Warriors From Risk-Averse Commanders and Their Lawyers

What are rules of engagement?

Rules of engagement are a device used by a commander to set forth the parameters of when, how, for what duration and magnitude and geographical location, and against what targets our forces can employ force, generally deadly force … in a theater of operations. …

How do rules of engagement used in the military compare to the body of law that backs it up?

The rules of engagement, strictly speaking, as they work in the military, contain a caveat … that nothing in these rules of engagement shall limit the right, inherent right, of self-defense.

And what's left unspoken but is legally significant, is the phrase, when confronted with "an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury." Because we're confronted with threats that may raise to the level of self-defense all the time. Most of those threats, however, don't require a deadly force response.

So the rules and the body of law that underpins those rules all concern discerning what is a reasonable response to an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. And the law that governs that certainly here in the United States is a constitutional Fourth Amendment understanding of what is reasonable. …

Why is there confusion over the right to self-defense? …

The confusion over the inherent right of self-defense doesn't come from the written word. It doesn't come from the law. …

The confusion over the inherent right of self-defense comes from assessing judgment-based shootings after the fact that, in the clear vision of 20/20 hindsight, may not appear to be reasonable when, in fact, by law and by tactics, they were. Let me give a prime example.

In January 2005, a vehicle approached a hastily constructed traffic control point on the route from downtown Baghdad to Baghdad International Airport. The vehicle approached the checkpoint in speeds close to 60 miles per hour, ignored flares and warning signs to slow down and halt, at which point the soldiers on the traffic control point reasonably perceived a threat, an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury, and engaged the vehicle.

In the clear vision of 20/20 hindsight, we learned that it was an Italian intelligence officer driving the vehicle who was, unfortunately, shot and killed. He was just taking a recently released journalist to freedom. It caused an ongoing international uproar. But that decision at the time the soldier [pulled] the trigger was, nevertheless, reasonable.

And that's where a lot of the confusion comes from. It comes from folks that don't understand the tactical dynamics of an encounter and wish to impose, one, either their Hollywood notion of what's reasonable, or two, try to judge the person by what is learned in the clear vision of 20/20 hindsight. ...

Can you talk about how the rules of engagement in Iraq compare to previous U.S. engagements?

I think that the rules of engagements in Iraq, compared to previous rules of engagements that I've been exposed to -- certainly in Desert Storm and earlier engagements -- are a lot clearer. I think they give affirmation to our troops to make the decisions at hopefully the lowest level possible.

But I think there is also a lingering confusion over that affirmation process. And we see that cause two problems. One, it can cause hesitation of our troops to engage threats that are indeed imminent. And then, the other side of the coin is if they're confused about who they should engage or where to engage, it can cause a shooting out of fear. ...

[What is positive identification?]

… Positive identification is a targeting term that's used against a declared hostile. For instance, we'll take a notional rules of engagement … where our command authority at a high level will designate terrorist group ABC as a designated hostile.

To engage that person, all one needs to do is ascertain positive ID -- in other words, to reasonably believe that that particular person is a member of the ABC terrorist group. We're unconcerned about whether or not that person is presenting an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. It matters little under the law or tactics.

For instance, if I'm a combat force of the United States, I can walk into a barracks room filled with ABC members sleeping in their bunks, and I can shoot them where they lie -- without concern whether they presented an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to me -- solely because of their status as a designated hostile under the rules of engagement. … That's where PID is relevant.

PID is nearly always irrelevant when it comes to responding to an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury in a self-defense capacity. I don't care whether or not the person shooting at me is a member of ABC terrorist group. I don't care if, in fact, they're an insurgent. All I care about is, by their actions, are they presenting an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to myself or friendly forces? That's all the legal authority I need to engage them. So too oftentimes this PID term is incorrectly sprinkled into what is, in fact, a self-defense scenario.

Now, what I do need to try to do is have aimed effective fire against an actual threat. That's where problems can arise. That is where actions by our adversaries of using human shields, using civilian houses, using mosques as platforms to fire from, can create nearly untenable situations for us as the good forces to respond to.

Because you could have an insurgent firing from behind human-shield walls of children and non-combatants. How do you return fire against that person without causing unnecessary civilian casualties? That's a very, very tough situation, and it's one that our forces face on a near daily basis in theater.

Gary Solis

Adjunct Professor at Georgetown Law School; Marine (Ret.)

The rules of engagement are much more general than most people realize. They are not tactical instructions. They don't -- and can't -- cover all situations. As general in nature as they are, they must leave some discretion to the individual soldier or Marine on the ground. …

Can you explain positive identification? …

PID, positive identification, is as the term implies: Before you can fire on an individual, you must positively identify that individual as representing a threat to you or your fellow Marines or soldiers. And if you cannot do that, then you are not supposed to fire on him or her.

The question is always, what constitutes PID? Some of us may have seen the shooting of a wounded individual in a mosque in Fallujah that happened some time ago. When one observes that, you may initially say, "Well, there's no PID there. There's no threat evident there. That looks like a murder in combat."

There was an investigation. And the question is not what I think or some other viewer thinks. The question is, what was in the mind of the Marine who shot the individual? Did he honestly and reasonably believe that that individual presented a threat to him and/or his fellow Marines? And, if he did, then no offense has been committed.

So it's not only an objective assessment, but then it's also a largely subjective assessment. … That's why one person may say yes; another person may say no. The question is, what did the shooter feel? …

When you're engaged in a firefight, a concept of positive identification, an awareness of the rules of engagement tend to fade. You're concerned with what's in front of you. You are acutely aware of the possibilities.

And if you see a fleeting target, you're going to fire on it. Now that doesn't mean that you are free to shoot anything and anyone that may appear during a firefight. But in a firefight, you don't have the luxury of considered thought. You don't have time for considered thought.

In a life-or-death action like that, you act and react. Now no one is going to, for example, turn and see a baby and say, "Oh, I think I'll shoot that child." It's conceivable that the child may be killed in the uncontrolled strobe-like melee of a firefight. But positive identification in a firefight -- you do the best you can.

Gary Myers

Attorney for Lance Cpl. Justin Sharratt

The rules of engagement have one fundamental underpinning, and that is that every soldier or Marine has the right to self-defense. That's the first and foremost element of the rules of engagement. And every Marine and soldier can tell you that. They have a little card and they can tell you what the card says.

The problem with the rules of engagement is that if you give those same group of young people a hypothetical circumstance and tell them how they would react to it, you get 20 different answers. …

The rules of engagement are, in combat, generally speaking, in the eye of the beholder, having as the first premise survival. Now, these young people know that a disarmed and helpless person is not to be shot on the one extreme. But, on the other extreme, if it's a sleeping enemy, identified as such, of course you can shoot.

My point is that the rules of engagement are an attempt to simplify an impossibly complex set of possibilities. And so you have to look at each case ad hoc and decide whether or not the conduct was reasonable.

Now, here's the problem. In military law, the only route to go, if you think that a crime has been committed, is to court-martial that individual, take him to trial. And if he has to defend himself and there's no one else around to testify, then he's got to take the witness stand to speak to the question of self-defense.

It is our view … that the doctrine of qualified immunity should apply to our soldiers. Call it "qualified combat immunity." It already exists for every policeman in the United States. The Supreme Court of the United States has said that if the conduct is reasonable there's no liability. And reasonableness is a objective standard.

We believe that that should apply to soldiers, so that a soldier, if charged, can file a motion to dismiss without having to go to trial on the basis that his conduct was reasonable. Now, this is not currently the law. But we believe it should be, because it requires the government to prove that his conduct was unreasonable. And we think that that's where this entire matter should lie before you actually go to trial.

I know this is sort of a technical discussion, but it's of critical importance to have a ground fighting force that believes that when it discharges its weapons it is not engaging in a criminal act. And I fear that the Haditha cases and other cases that have followed have given an impression to young ground troops that they, in fact, are at risk if they fire their weapon. And that does not augur well for an army, for a Marine Corps, that can be effective in the field. …

… Over the course of this war our tactics have changed. Our understanding of the strategy has changed. How have these rules of engagement changed as well?

Well, frequently they're local rules of engagement that address a given set of circumstances. Fallujah II is an example of where the rules of engagement were dramatically relaxed to allow for Marines to fire much more liberally, shall we say, than they would be in other environments. But Fallujah II is considered by the Marine Corps, and by those who were associated with it, to be one of the most significant battles in the history of the Marine Corps. And so the rules of engagement there were relaxed.

Rules of engagement are promulgated on the local level and so there are many rules of engagement that adjust to individual circumstances. So it's impossible to tell you there hasn't been a generic shift in the rules of engagement. The fundamentals are still the same -- right to self-defense, positive ID, so on. But there are, under certain circumstances, alterations in the rules of engagement to take into account the anticipated operational circumstance.

Josh White

Military Affairs Correspondent, The Washington Post

… Can you talk about the tension and confusion [in the ROEs] in fighting a counterinsurgency?

One of the chief tensions of fighting a counterinsurgency under the new rules is that troops are trained to defend themselves and that they have an absolute right to engage a target if they feel that their life is in danger. That is up against the idea that it is of vital importance to protect civilians from being engaged.

Now where this really shows itself is at checkpoints. In the early part of the war, the United States was responsible for a number of checkpoint shootings, where cars would drive up to a U.S. military checkpoint, and maybe not understand exactly what they were supposed to do, and in failing to stop, or speeding up, or acting erratically, U.S. troops viewed that as threatening behavior and, in some cases, killed people who were simply not understanding what the rules were. They killed a number of civilians in that manner.

Commanders were especially attuned to that issue and wanted to make sure that U.S. troops understood that simply because someone is acting erratically doesn't necessarily mean that they're a suicide bomber. It may mean that they're confused. And in weighing the self-defense issue with the desire not to wantonly kill people there's a difficult gray area in the middle that each and every member of the military has to [confront] when they're in combat. And generally speaking, I think, commanders will side with the decisions that their troops make as long as they make them in a rational, thought-out, trained way.

… How are the rules of engagement different in an insurgency than in conventional conflict?

The rules of engagement are not terribly different. The rules of engagement that we put into place as we crossed the berm going into Iraq in '03 are exactly the same rules of engagement that [are] in place today.

At its essence, what the rules of engagement say are that if you feel threatened by an enemy force or by an incident that's taking place in front of you, you are authorized to engage. And that hasn't changed. Nor should it change, be it a conventional environment or an insurgent environment. …

No comments:

Post a Comment