Kingdom of Saudi Arabia vs. Islamic Republic of Iran

A proxy war in the Middle-East

In Syria, where a civil war has been raging since 2011, the government is led by the Alawite clan of Bashar al-Assad. Alawites are often considered as a branch of Shia, though there is a debate among Sunni Muslim scholars about their belonging to Muslim faith. The government also has the support of most religious minorities in Syria such as Christians and Druze, as well as a part of the Sunni middle and upper class. Iran has been involved very early in the conflict, by supporting its Lebanese ally the Shia Hezbollah whose presence has been increasing since 2012. Besides Hezbollah, Iran has stepped up their support to the Assad government by supplying technical assistance, weapons, elite troops and financial support. Today, Iran is with Russia and Hezbollah, the al-Assad government’s strongest support in fighting against Islamist insurgents, the Free Syrian Army and Jihadists.

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia has been heavily helping insurgents, which are overwhelmingly of Sunni faith. The kingdom is a strong support for the rebel Islamic factions: Islamic Front, Ahrar-al-Sham, as well as Jaysh-al-Fath or Jaysh al-Islam rebels alliances, and the FSA Southern front in the South. While Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian al-Qaeda branch, is also part of this alliance, it is mainly supported by Qatar. The Islamic State is officially an enemy of Saudi Arabia but receives funds and recruits from private Saudi sources.

Iraq

Iraq has a Shia majority and has been experiencing a kind of democratic system leading Shia political parties to hold the power. Although theoretically shared with Sunnis and Kurds, the Iraqi government is mostly considered by Iraqi Sunni population as well as by Middle-Eastern states as a Shia government strongly influenced by Iran. This situation has led to a permanent volatile situation between Shia and Sunnis, to the Jihadist and Islamic State insurgency, as well as to the de-facto autonomy of the Kurdish part of the country. The Islamic State took control of large parts of the country in 2014 in the Sunni population areas, and the risk of the country collapsing has led to an increased Iranian presence and assistance for the Iraqi army and for Shia militia and paramilitaries. Although not supporting the Islamic State in Iraq, Saudi Arabia favors Sunni opposition.

Bahrain

Bahrain is a Constitutional Monarchy with a Shia majority of 70%, and the ruling Monarch family belonging to the Sunni faith. The kingdom has experienced a wave of protests in 2011 which was presented as a Shia uprising but had mostly social and economic roots. The situation brought Saudi Arabia and the Gulf cooperation council, a cluster of six Gulf Petro monarchies, to send troops to restore orders, and as a result of the security and appeasements measure, the protests decreased gradually in the following months and years. However, a Shia opposition, which is believed to be instrumented by Iran, continued to lead protests, boycotting the 2014 elections for the Council of Representatives. Despite the boycott, 14 Shia out of 40 representatives were elected.

Yemen

Yemen is, as Syria, a country experiencing a civil war between the forces loyal to the government of Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi, based in Aden, and a Shia insurgency from the Houthis in the North-West of the country. Those chased the legal government from Sanaa in February 2015, and hardly seized the remains of the legal government from Aden in March 2015. This led the Saudi Government to build up a military alliance, Operation “Decisive Storm” and to start a bombing campaign over the Houthis troops. In the meantime however, Iran stepped up their support to the Houthis, leading to a very volatile situation with frequent skirmishes in the border area with Saudi Arabia. The situation in Yemen is worsened by a Jihadist insurgency linked to the Islamic State and al-Qaeda in the center of the country, further weakening the Saudi-backed government.

This proxy war is also raging in Lebanon where tensions between Hezbollah and Sunni political parties have increased following Hezbollah’s strong involvement in Syria. Although the government is led by a moderate Sunni since 2014, Tammam Salam, the Hezbollah has a strong presence of eight ministers and the support of a part of the Christians from Michel Aoun, and they are directly supported by Iran, while the Said Hariri camp is supported by the USA and Saudi Arabia and is in favor of the Syrian opposition. Although having to share the power with their enemies, the Hezbollah are the strongest military faction in Lebanon, and are therefore leading the fight against Jihadists in Shia areas while leaving the Lebanese army dealing with those Jihadists in Sunni areas such as Arsal near the Syrian border.

The opposition between Iran and Saudi Arabia is the opposition of two regional powers, leaders of two concurrent faiths of Islam. In the aftermath of the American intervention in Iraq and of the Arab Spring, the proxywar by its intensity has overshadowed the Israel-Palestine conflict and spread all over Middle-East, involving more countries, more factions, and paving the way for violent Jihadist insurgency.

Resisting the drumbeat

When have we heard more hysterical commentary than during this past week, a week of incomplete sentences and excited spluttering? Ironically, only the President remained calm; only his remarks regarding ISIS’s threat to the US made sense; and, perhaps for that reason, the media and political establishment have excoriated him and deprecated the administration resoundingly.

Meanwhile, a perfect storm is picking up speed in Syria, where a civil war broke out four and a half years ago, in response to a citizens’ uprising against Bashar al-Assad during the multi-national Arab Spring. I remember seeing an interview with some moderate rebels then: they were dismayed at the US’s failure to help them and predicted that disillusionment would encourage the growth of anti-Western extremism. And so it has.

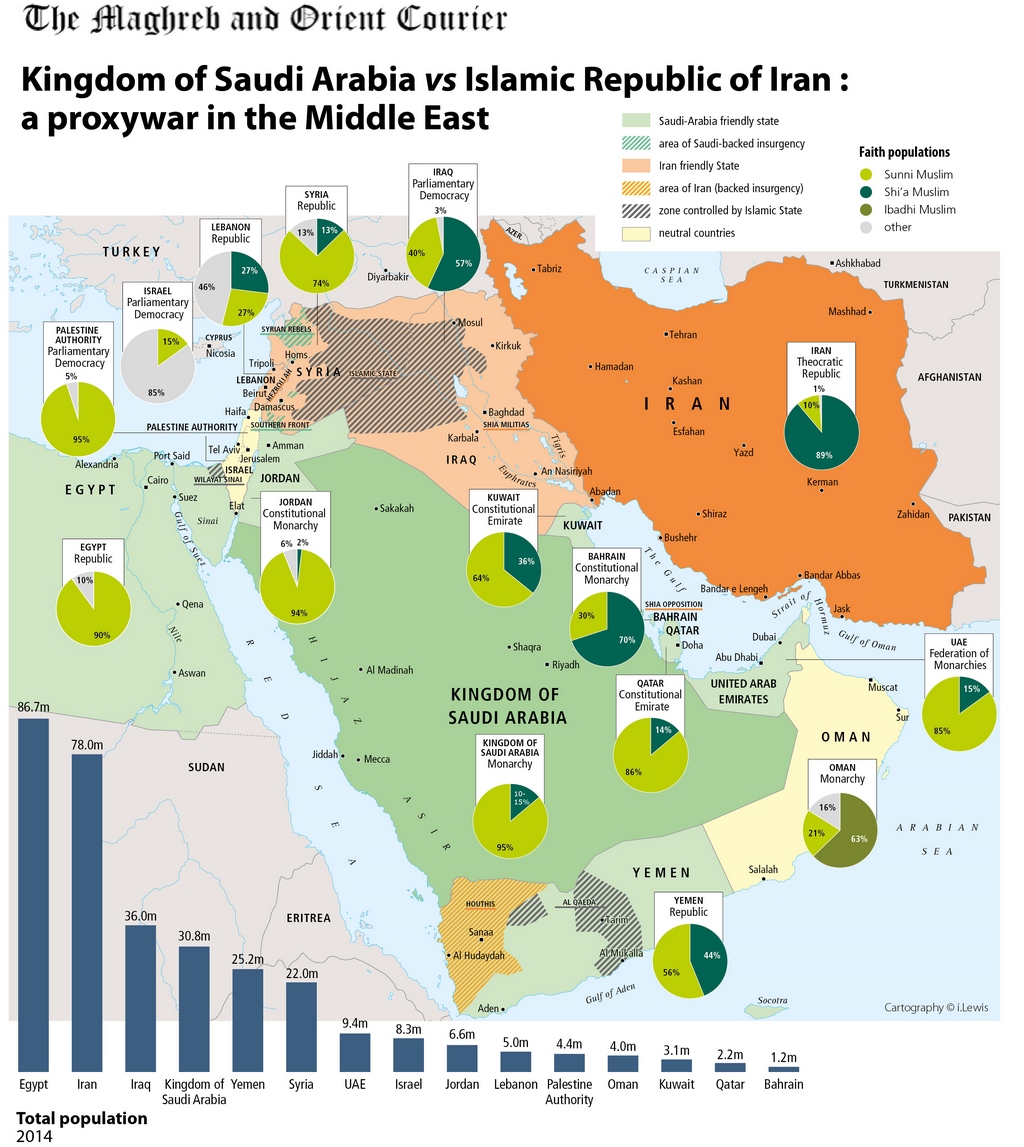

Since that ‘simpler’ time, Syria has become the theater where at least three wars are raging simultaneously. First, there is the increasingly sectarian civil war aimed at deposing the intractable Assad. Second, a war within a war is being waged, as the stateless guerrilla group ISIS attempts, in Syria and elsewhere, to establish a retrograde caliphate that it justifies in the name of Islamic purity. Finally, the Syrian war is a proxy war, with numerous other powers overtly or covertly aiding the principal combatants, attempting to further their own interests by investing in the triumph of one or the other side. The outside players include Iran, Russia, and the Lebanese-based group Hezbollah on the Syrian government’s side, and Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the US, the UK, and France on the opposition side. (For more on the war’s history, see this BBC News summary; also this map of Middle-Eastern involvement at The Maghreb and Orient Courier.)

The opposition has the weaker hand, because its principal aim is to bring down the Assad regime; yet no one can imagine who could bring order to Syria if Assad were gone. The so-called ‘moderate’ rebels fighting for democracy have long since been overwhelmed by militants from all over the world, and especially by Sunni forces fighting to bring down Assad’s Alawites and attain a theocratic victory. Westerners who think this war is still primarily about democracy and self-determination have it wrong. Re-establishing civil order will involve either the installation of a puppet government with a new strongman or a return to the status quo ante bellum.

Tactically, the conflict has morphed into a type of total war that is difficult to categorize, though, sadly, many of its most brutal elements (chemical warfare, the bombing of civilian populations) have occurred in modern wars before. The tactics of the Islamic State (which of course is a fantastical misnomer, as the force does not constitute a state at all), however, are novel in that they combine Western-oriented terrorism with transnational guerrilla warfare aimed at further creating anarchy in and beyond the territory that ISIS is intent on overtaking.

The New York Times published an excellent graphic feature highlighting how ISIS’s terror activities complement their geographically focused war aims. Precisely because ISIS is not a state, it wishes to promote anarchy as well as to break up the influence of the West and exorcise the Western narrative that has shaped and justified our involvement in the affairs of many Muslim-populated societies.

In the wake of the Paris attacks, the pressure is on the Obama administration to step up the fight against ISIS in Syria, to send ground troops and commit more air and fire power to a multi-sided conflict already fraught with too many antagonistic parties. The pressure is all the greater given that the presidential race is in full swing. Republican candidates, eager to talk tough, are vying to out-do one another with fantastical visions of military aggression whose virtues are merely quantitative.

President Obama did a good job last week of reminding everyone that ISIS is not a state but a more amorphous and unconventional enemy. At a press conference during the G20 summit in Turkey, the president astutely rejected the idea of being further drawn into a conventional war, reminding his listeners that conventional tactics will not work against this unconventional enemy.

The gravest threat that ISIS poses to the US is the incitement of terror. Here’s hoping that Americans can resist the drumbeat and refrain from over-reaching in the Middle East, instead choosing to devote themselves to the twin causes of domestic safety and peace.

WikiLeaks Shows a Saudi Obsession With Iran

July 16, 2015New York Times - For decades, Saudi Arabia has poured billions of its oil dollars into sympathetic Islamic organizations around the world, quietly practicing checkbook diplomacy to advance its agenda.

But a trove of thousands of Saudi documents recently released by WikiLeaks reveals in surprising detail how the government’s goal in recent years was not just to spread its strict version of Sunni Islam — though that was a priority — but also to undermine its primary adversary: Shiite Iran.

The documents from Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Ministry illustrate a near obsession with Iran, with diplomats in Africa, Asia and Europe monitoring Iranian activities in minute detail and top government agencies plotting moves to limit the spread of Shiite Islam.

The scope of this global oil-funded operation helps explain the kingdom’s alarm at the deal reached on Tuesday between world powers and Iran over its nuclear program. Saudi leaders worry that relief from sanctions will give Iran more money to strengthen its militant proxies. But the documents reveal a depth of competition that is far more comprehensive, with deep roots in the religious ideologies that underpin the two nations.

Recent initiatives have included putting foreign preachers on the Saudi payroll, building mosques, schools and study centers, and undermining foreign officials and news media deemed threatening to the kingdom’s agenda.

At times, the king got involved, ordering an Iranian television station off the air or granting $1 million to an Islamic association in India.

“We are talking about thousands and thousands of activist organizations and preachers who are in the Saudi sphere of influence because they are directly or indirectly funded by them,” said Usama Hasan, a senior researcher in Islamic studies at the Quilliam Foundation in London. “It has been a huge factor, and the Saudi influence is undeniable.”

The Saudi government has made no secret of its international religious mission, nor of its enmity toward Iran. But it has found the leaks deeply embarrassing and has told its citizens that spreading them is a crime.

It said last month that the documents were related to an electronic attack in March on the Foreign Ministry that was claimed by the Yemeni Cyber Army, a little-known group believed to be backed by Iran.

WikiLeaks mentioned the attack when it released the documents.

The trove mostly covers the period from 2010 to early 2015. It documents religious outreach coordinated by the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs, an interministerial body that King Salman dissolved in a government overhaul after his ascension this year.

The Foreign Ministry relayed funding requests to officials in Riyadh, the Interior Ministry and the intelligence agency sometimes vetted potential recipients, the Saudi-supported Muslim World League helped coordinate strategy, and Saudi diplomats across the globe oversaw projects. Together, these officials identified sympathetic Muslim leaders and associations abroad, distributed funds and religious literature produced in Saudi Arabia, trained preachers and gave them salaries to work in their own countries.

One example of this is Sheikh Suhaib Hasan, an Indian Islamic scholar who was educated in Saudi Arabia and worked for the kingdom for four decades in Kenya and in Britain, where he helped found the Islamic Sharia Council, according to a cable from the Saudi Embassy in London whose contents were verified by his son, Mr. Hasan of the Quilliam Foundation.

Clear in many of the diplomatic messages are Saudi fears of Iranian influence and of the spread of Shiite Islam.

The Saudi Embassy in Tehran sent daily reports on local news coverage of Saudi Arabia. One cable suggested the kingdom improve its image by starting a Persian-language television station and sending pro-Saudi preachers to tour Iran.

Other cables detailed worries that Iran sought to turn Tajikistan into “a center to export its religious revolution and to spread its ideology in the region’s countries.” The Saudi ambassador in Tajikistan suggested that Tajik officials could restrict Iranian support “if other sources of financial support become available, especially from the kingdom.”

In 2012, Saudi ambassadors from across Africa were told to file reports on Iranian activities in their countries. The Saudi ambassador to Uganda soon filed a detailed report on “Shiite expansion” in the mostly Christian country.

A cable from the predominantly Muslim nation of Mali warned that Iran was appealing to the local Muslims, who knew little of “the truth of the extremist, racist Shiite ideology that goes against all other Islamic schools.”

Many of those seeking funds referred to the Saudi-Iranian rivalry in their appeals, the cables showed.

One proposal from the Afghan Foundation in Afghanistan said that it needed funding because such projects “do not receive support from any entities, while others, especially Shiites, get a lot of aid from several places, including Iran.”

Reached in Kabul, the Afghan capital, one of the center’s founders, Wakil Ahmad Mutawakil, acknowledged that the group had appealed for Saudi funding but said that it had received none.

The kingdom has at times interfered directly with Iran’s outreach.

A Beirut-based manager of Al Alam acknowledged that the channel had faced Saudi pressure since 2010, which had succeeded in getting two Arab satellite providers to drop the channel.

“We are broadcasting normally” via European satellites, the manager said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss private company matters. “The only disruption we have is when we broadcast a show about Bahrain.”

The Saudi Embassy in Sri Lanka reported a meeting between the Iranian ambassador and a group of religious scholars, noting that it began at 7:30 p.m.

Elsewhere, the kingdom intervened against foreign officials it perceived as threats.

After the president of the International Islamic University of Islamabad in Pakistan, Mumtaz Ahmad, invited the Iranian ambassador to a cultural week on campus, the Saudi Embassy called Mr. Ahmad to express “its surprise,” according to one cable, suggesting that he invite the wife of the Saudi ambassador instead.

A faculty member at the university said that Mr. Ahmad, a political science professor with a doctorate from the University of Chicago, had clashed with conservative faculty members for trying to reduce Saudi influence on campus.

After Mr. Ahmad resigned as president in 2012, the Saudi ambassador worked with the president of Pakistan at the time, Asif Ali Zardari, to have a Saudi citizen named as university president, according to the faculty member.

“In the end they won,” said the faculty member, who spoke on the condition of anonymity so as not to anger his employer.

The cables named 14 new preachers to be employed in Guinea and said contracts had been signed with 12 others in Tajikistan.

Another cable said the Foreign Ministry was studying a request from an Islamic association near the Iranian border in Afghanistan to pay local preachers to spread Sunni Islam.

Some of the costliest projects were in India, which Saudi Arabia sees as a sectarian battleground.

Cables indicated that $266,000 had been granted to an Islamic association to open a nursing college; $133,000 had been used for an Islamic conference; and another grant went to a vocational training center for girls.

King Abdullah, who died in January, signed off on a $1 million gift to the Khaja Education Society, and a smaller amount went to a medical college run by Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen.

A member of the first group, Janab Moazam, confirmed that it had been granted the money and said that half had already been delivered. An official from the second group, Abdullah Koya Madani, confirmed that the group had received Saudi funding.

Even humanitarian relief is sometimes sectarian. In 2011, the Saudi foreign minister requested aid for flood victims in Thailand, noting that “it will have a positive impact on Muslims in Thailand and will restrict the Iranian government in expanding its Shiite influence.”

Elsewhere, Saudi Arabia sees its religious work as a way to improve its reputation. The Saudi ambassador to Hungary requested $54,000 per year for an Islamic association as well as for authorization to found a cultural center. One cable said such aid would undermine extremism and “play a positive role in portraying the beautiful and moderate image of the kingdom.”

No comments:

Post a Comment